BATTLE OF BROODSEINDE

For the next stage of his carefully planned campaign, General Herbert Plumer had his eyes set on one of the German army's main strongpoints on the ridgelines about Ypres.

And it was to once more be the Anzacs who were given the task of taking it.

A number of small hills, or spurs, run down from the main Passchendaele ridgeline, among them the Broodseinde Ridge, which acted as regimental headquarters for the German forces in this sector of Ypres and an observation post overlooking the entire salient.

The Australians in I Anzac were given the task to make the assault on Broodseinde itself. II Anzac, including the Kiwis, were to be positioned just north of I Anzac and given the target of Gravenstafel Spur. Gravenstafel was the lower of two spurs jutting out of the Passchendaele ridgeline in this area. The New Zealand Division was to take the eastern slopes of the spur, known as Abraham Heights.

Colonel Hugh Stewart, who wrote an impressively researched history of the war published in 1921 based on extensive original sources and his own observations having served with the NZ forces in Gallipoli and on the Western Front, gives a description of this formidable target which the Kiwis were to face: valleys and ridgelines, chequered with German strongpoints and crisscrossed with streams. “From the main ridge, on whose plateau in front of II Anzac lay the shattered houses of Passchendaele, various small subsidiary spurs run out north-westwards, separated from each other by the headwaters of the sluggish streams characteristic of this part of Flanders. Two such spurs faced the New Zealand Division, one immediately confronting their trenches, the other northwards behind it. The nearer and more southerly one of these rose just over the small stream of the Hanebeek, which lay immediately beyond our front line. It was called the Gravenstafel Spur. Soon after it projected from the Passchendaele Ridge its even crest was broken by an isolated almost imperceptible rise called Abraham Heights; thereafter it fell gradually towards the ruins of [the villages of] Gravenstafel and Korek, and beyond them to the plains. As the Hanebeek drained the slopes which faced the New Zealanders, so its reverse slopes to the north were drained by another stream which in its upper part was called the Ravebeek but presently, after receiving some small tributary channels, the Stroombeek. On the other side of its valley, standing further back and further to the north from the New Zealand lines, was the second spur which jutted out from the main Passchendaele ridge. This was the Bellevue Spur.” Bellevue – the ridgeline that would prove so fateful later that month.

In all, the NZ Division was allocated a front of just under two kilometres in length and this bite attack was to seize one kilometre of enemy held territory, then dig in and consolidate their position. If they succeeded, it would take the British forces back to an old line it had last held in 1915.

Facing them were the German 4th Bavarian Division.

There was to be no preliminary bombardment over preceding days this time. Instead there would be a single devastating artillery barrage just before the troops were to attack.

First and Fourth Brigades were selected to be thrown against Abraham Heights. Four battalions would lead the charge – from First Brigade the battalions 1st Auckland with Bert in its ranks and 1st Wellington, and from Fourth Brigade the 3rd Otago and 3rd Auckland battalions. They would seize the first objective and then be leapfrogged by four more battalions – 2nd Auckland and 2nd Wellington from First Brigade and 3rd Wellington and 3rd Canterbury from Fourth Brigade, who would surge onto the second objective.

To the right would be the Australian divisions, on the left British divisions.

On the evening of 3 October, the weather broke, and it rained without stopping for four days and four nights. As every Allied soldier knew, the Germans could command rain when they needed it.

Into the early hours of 4 October 1st Auckland prepared for the assault by moving into ground facing a landmark known as Cluster Houses – bombed out farm buildings – and behind what had once been the picturesque Hanebeek Creek. A start tape – an actual, real piece of tape laid on the ground – marked out for the New Zealanders where they were to position themselves and hastily dig temporary trenches. Bayonets were fixed to rifles. They crouched down within yards of Winzig and Aviatik, two more farm houses, these ones barricaded and used as fortresses by the Germans, from which they were continually raked with machine gun fire. All waited anxiously for zero hour – 6am.

Stewart says: “It was a dark night but exceptionally quiet lulled by the absence of a preparatory bombardment. The New Zealand companies were guided forward to their positions without noise or confusion. A platoon from each battalion in the posts was extended at 25 yards' interval to show the alignment. During this assembly the enemy ... machine gun activity caused several casualties. The men were not overloaded. The battalions for the Red Line carried 120 rounds of ammunition and the attackers of the Blue Line 170, One Mills grenade had been found sufficient for the present form of fighting. The men were heated, however, by the march and by the construction of their shallow trenches. Now, as they knelt down on the oozy soil in such protection as these shelters and shell holes afforded, a clammy drizzle began to fall, and a strong westerly wind chilled them to the bone.”

New Zealand troops move into position in the early morning on 4 October 1917

The troops waited while the clock ticked down.

Burton adds his vivid recollection of those long moments: “Scarcely anyone has slept, all are chilled to the bone. Breakfast has been a few mouthfuls of bully beef, dry bread and water. Officers and NCOs move round, giving final instructions; the men stand quietly about, waiting with nerves somewhat on edge after the ordeal of the night. Within a few minutes they will be passing through the deepest and most soul-searching experience that men can undergo.”

Suddenly at 5.20am a heavy German artillery barrage erupted. One historical view is that by chance the opposing German army under General Sixt von Armin had chosen that morning to launch their own bold attack to push the Allies back. However, more recent research points to the Germans simply strengthening their front lines in preparation to meet an expected attack. Whatever the purpose, the Germans had massed in their forward positions and at the same time von Armin had unleashed his own barrage. But with the Kiwis themselves hunkered into forward positions, most of the German shells fell behind the New Zealanders.

As 6am struck, the British heavy shell fire erupted in return, New Zealand machine guns rattled into action and many of the Germans massed in their forward positions further up Gravenstafel spur were caught out and killed. Stewart, quoted later, gives a dark description of the bloodshed that the Kiwis would find when they made it to the German lines.

Now the Aucklanders, Bert among them, with Gordon Coates his commander in 3rd Company, leapt into action. But their first obstacle was not the Germans. Instead it was the creek immediately before them. Constant heavy shell fire had turned Hanebeek Creek from a running stream into a wide bog, passable only at certain places where they could find a route. Stewart says each battalion was meant to be attacking with a two-company frontage but were forced to move section by section in single file “where the little ridges between the lips of the shell-craters provided the sole tracks for advance.” As Kiwi divisional commander Major General Sir Andrew Russell later said: “The mud is a worse enemy than the German.”

The Germans were firing their own artillery in counter attack, hitting Hanebeek Creek. Burton said of it: “Crossing this swamp was a terrible strain, as progress was so very slow. The German shell fire was playing with remarkable accuracy on the narrow tracks. Only the softness of the ground, in which the shells failed to explode or were smothered, saved the attacking troops from very severe losses.”

The Broodsiende battlefield. This photo from 24 October 1917 shows the conditions Auckland faced. This captured pill-box was at a place dubbed Garter Point.

Once on the other side of Hanebeek, Plumer, with all his careful attention to detail, had arranged for four distinct barrages to take place, marching up the slope ahead of the Kiwis. The first began 150m in front of the starting tape. The Kiwis were to rush forward, with the barrage lifting and moving up another 50m to touch down once more with its torrent of shells. It would continue to move forward like this up the slope every two minutes until the Kiwis had made it 200m up the side of the Gravenstafel spur. Then, in recognition that the going would be getting increasingly tough heading uphill, the barrage would slow down to shift forward 50m every three minutes. This would take the New Zealanders to the first objective – designated Red Line – a line on a map running approximately along the crest of the ridge just short of Gravenstaffel Village.

It was a well thought out plan. As an officer of the NZ Medical Corp, Andrew Robert Dillon Carbery termed it: “A limited advance with unlimited explosives to blast out a way. If the weather held it must succeed.”

Across the Hanebeek swamp, Stewart says the Kiwis looked upon a “country, dismal and war-scarred” with “stunted remains of copses” and “here and there levelled heaps of bricks and stones on the spurs and in the valleys told of farms and villages.” He goes on to say: “In the vicinity of most of these houses and at all points of importance the Germans had constructed numerous pill-boxes.” Despite Plumer’s barrage, those German pill-boxes remained intact. Immediately before 1st Auckland lay Aviatik Farm and Dear House. As the Aucklanders closed up the hillside the German machine gunners cut men down. Stewart: “Under a blast of machine gun fire from Aviatik Farm and the shell holes the first line of the attack withered away.” Light trench mortars used by the infantry were swiftly deployed, Mills bombs thrown and the German strong points were taken.

It was round this point the Kiwis also made the gruesome discovery of the lines of Germans who had been manning their forward trenches and were decimated by the British artillery fire. Stewart writes: “On the 1st Auckland front alone were about 500 corpses, and generally along the whole line every shell hole held 1 to 4 dead Germans. Some of the survivors fought pluckily with rifle fire, but when it came to bayonet work and close quarters, neither physically nor morally were they a match for their assailants.”

But the Aucklanders remained under pressure. In a line with Aviatik and Dear House lay Winzig, “a nest of dugouts” just to their left, inside the British sector of the attack plan. “Machine guns from here played on Auckland's left and threatened to arrest progress.” Technically, the Aucklanders should have ignored Winzig because it was outside their sector, leaving it to the British, but they made a decision to attack it and shut it down. As Stewart said, they needed to protect their flank, but also, they were “partly attracted by the magnetism which fire exerts over brave troops.” So, the Aucklanders took the first step into the British sector – a decision which would lead them further and further astray.

The leading Aucklanders first through Hanebeek were 15th and 16th Companies. As they charged Winzig, both Company commanders were killed. Finally, 3rd Company cleared Hanebeek. Coates sent his men surging forward to reinforce the assault on Winzig. It was a “bitter fight” said Burton. “The garrison of this strong point were very brave men and fought with desperate courage.” But at last platoons from 15th and 16th managed to get high enough up the slope to outflank them, a Lewis gun was brought in to play. Mills bombs were thrown. Winzig fell.

With the death of his fellow Company commanders, Coates now found himself one of the few senior officers still standing and he had to take charge of the entire battalion attack now. As he quickly surveyed the lie of the land around him, he saw the situation on the left flank was worsening. The British 48th Division troops had suffered heavy casualties and were unable to go on, leaving the Aucklanders exposed to enemy fire with no one attacking the German strongpoints there. Coates now had no choice; the Aucklanders having moved this far into the British sector had to continue and launch a full assault into the British battle sector to shut down all threats there as well as take the New Zealand objectives.

Best estimate of the 1st Auckland attack at Gravenstafel.

Bert was by now a signaller and about to prove his worth. With no telephone lines or radios, the only way Coates had to send his orders to the many platoons of men now under his command and keep the battalion attack coordinated and battalion HQ informed, was to use a runner – a perilous exercise for the man chosen, he had to traverse the battle field, braving shells and enemy fire, to keep the flow of information constant between Coates, the platoon junior officers and NCOs and Batt HQ officers. Bert was his platoon’s signaller, but Coates turned to him and gave him a quick field promotion: he was now Company signaller, and in this instance, signals runner – the man tasked with keeping the battalion on track.

The Aucklanders were being hit by fire from another barricaded strong point at Albatross Farm. Coates’ first order was to swing 3rd and the other companies into the gap left by the British, then push far forward to clear Albatross and then another German strong point, designated Winchester, leading them deeper and deeper into the Stroombeek valley

Coates’ decision to move into the British sector seems to have attracted criticism in some accounts, which record with a note of disapproval that 1st Auckland “drifted to the north” in the early stages of the advance. But any criticism is unfair and doesn’t factor in the realities Coates was encountering.

However, Stewart commented that 1st Auckland “paid severely for trespassing into the Stroombeek valley” and under machine gun fire from yet another fortified farm, this one called Yetta Houses, “suffered more heavily than the other battalions.”

Ultimately, they ended up clearing the entire battle field to the Red Line in the British 48th Division’s allotted sector.

The diversion into the British sector by Auckland had caused a corresponding swing in 1st Wellington as they sought to keep touch with Auckland on their flank. It also left the Wellington Battalion to clear most of First Brigade’s sector themselves, linking up with some troops from Fourth Brigade’s 3rd Otago Battalion.

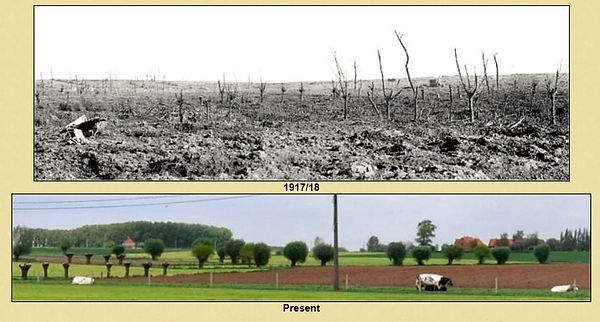

This interesting comparison shows a photo of the Broodseinde Ridge that the Anzacs attacked in 1917 compared to how it looked in 2009. The photo montage was created by Australian Peter Morrissey who has carried out award winning study of WWI battlefields.

Alongside the stiff resistance by some Germans during the battle there were also those who had no more stomach to fight, cowed by the barrages and the sight of the remorseless Kiwis continuing forward no matter how many of them fell to the pill-box guns. Burton writes about such German defenders, saying of them that their: “knees weaken and they cannot run, fear becomes terror and terror panic and the panic a madness. Men wrap oilsheets round their heads and cower down dumbly expectant of death – they are no longer men but driven cattle. Some are shot, some are bayonetted, some dragged out and half-kindly, half-contemptuously sent back to the rear without escort.”

In a letter to his brother Frank, Bert describes an incident which isn’t clearly dated, but in all likelihood refers to the Gravenstafel action, as he encountered Germans, just as Burton depicts them, in one of the many dugouts or farm buildings as he moved around the battle zone.

“I shouted to them to come out but they took no notice and I fired a shot into the ground alongside of them to draw their attention, but still no response so I gave one of them a prod with a bayonet and out he came holding up his hands and jabbering something in German, which of course I could not compree. I pointed to his mate and he turned him over, but I could see he was mortally wounded so I let him alone and I beckoned to him to come out of the hole, but he began gesticulating and I could see that he thought I would bayonet him, as evidently they are told that we take no prisoners, and he was scared out of his wits by our shell-fire like a rabbit. He was little more than a boy. I made him drop his equipment and I pointed in the direction of our lines where two big Square-heads were going for their lives with their hands up and I said ‘Allay tout de suite’ and off he went with his hands above his head.”

Prisoners were always sent back behind British lines where big cages were set up to hold them. More than 1000 prisoners were taken by the Kiwis in the Broodseinde battle. Bert’s observation on the youth of the German he encountered was shared by other Kiwis in the battle – many wrote later that numbers of the German soldiers were just boys of 17 or 18, in a miserable condition, scared, occasionally in tears.

Having reached Red Line in the British sector, Coates spread the battalion out, moving what men he could afford back along the line until they linked back up with their fellow battalion from First Brigade, 1st Wellington, inside the New Zealand battle sector. Across this wide front they were attempting to secure, the Aucklanders dug in.

Stewart: “Along the whole of the Red Line, as soon as the immediate front was cleared, every man worked with a will at consolidation. Down in the Stroombeek flats 1st Auckland soon struck water, but on the slopes the other battalions found good soil, and by the time that the barrage moved forward, though the line was not yet connected, the different posts were 4 or 5 feet under cover.”

Bert writes: “Shells were lobbing everywhere and bullets cracking, but no one took any notice of them and the chaps were sniping at the retreating Huns as coolly as they were shooting rabbits. Away in the distance, Huns could be seen going for their lives. However, we reached our objective and dug in, in less than no time.”

Exhausted Aussie stretcherbearers collapsed on Broodseinde Ridge.

The two battalions from Fourth Brigade, south of the Aucklanders and Wellington, were meanwhile tackling Abraham Heights itself. They surged forward but were then held up by a large pill-box known as Otto Farm. Eventually they outflanked it and threw Mills bombs in, capturing it.

There were also some hotspots of German resistance left for the leapfrogging battalions to mop up as they started arriving, ready for their charge forward.

Australian soldiers in newly dug trenches on Broodseinde Ridge as they consolidate to hold the newly won ground. This is to the right of the Kiwi battle sector.

Despite all the impromptu changes to plan, within 50 minutes of beginning the assault, Red Line was reached across the entire New Zealand sector and, courtesy of Auckland, the British sector. Plumer’s barrages lifted altogether now to allow the Kiwis to consolidate and secure their positions.

They were given an hour to ensure their lines were in order, then 150m ahead of Red Line the barrage rained down once more and moved on at a rate of 50m every four minutes. This was the signal for the charge for the second objective, designated Blue Line, another 500m further on from Gravenstaffel Village at the foot of the Bellevue Spur, which lead up to Passchendaele itself. Burton describes it as “500 yards of shell holed country to cross under rifle fire”.

The Kiwi leap frog battalions from First and Fourth Brigade took up the attack, pushing forward now, along the eastern slopes, taking down more pill-boxes and subduing Berlin farm and Berlin Wood till they reached Blue Line.

It had been the best example yet of the merits of Plumer’s precise planning, but as Burton shows, such success was not inevitable, there were moments of uncertainty when the battle could have gone either way and the Kiwis could have fallen short.

Burton describes one such critical moment which he calls one of the “stiffest fights” of the day as the leapfrog units went forward and encountered a strongly held trench right on Blue Line at the foot of the rise up to Passchendaele itself. Due to the nature of the attack, with small episodes of combat taking place all over the battle zone, there were only 40 Kiwi soldiers in the group that found themselves facing this particular 100m final stretch to the trench – outnumbered four to one by the German defenders. And with Plumer’s barrage for this area now lifted, they were in the open with no cover, losing men all the time to the German fire coming at them from the trench. Regardless, and showing a grit that came to define the Kiwi troops, building their reputation as a relentlessly attacking division, the men charged. Burton says: “It was an impossible task, and if the Germans had kept their nerve, every one of the attacking party would have been shot down and with the bare hillside before them the enemy could have developed a local counter attack which might well have crumpled up the NZ forward line. As it was their nerve failed at the critical moment and they surrendered.”

Gravenstafel Spur was taken. It was now just 9.30am. The success of the Kiwis had been breathtaking.

One Kiwi solider summed up the attack as “a day I will not forget for a lifetime.”

Plumer’s final barrage rained down 150 yards out from Blue Line, “during the vital period of consolidation protecting the infantry while they dug new trenches.” Then it lifted. The 68 Lewis machine guns of the New Zealand division meanwhile were brought up into position and laid down their own cover, out to 500m beyond the new line, ready to help stop any counter attacks.

And the Germans did counter attack, furiously – starting at 8.15am in some positions, then again at 10am, noon and 2pm, 4pm and 8pm.

1st Auckland moved up to help secure Blue Line, which was now the newest and most forward British frontline. They held grimly on to their position through the rest of that day, through the night and on into the following day.

This is a photo of Canadian troops digging into their Blue Line further up the ridgeline in a battle in a few weeks' time, but shows the conditions the Aucklanders faced - a frontline little more than a hole dug into a sea of mud.

Stewart said October 5 “dawned grey and dismal, and chilly rain fell all but continuously during the day. The mud and water in the forward trenches reached almost to the men's knees.”

Bert remained busy, fighting alongside his comrades to repel the Germans when needed and then struggling to get the wires sorted for telephones which would have been rapidly installed by the Engineers division to give Battalion HQ better communication with the front. At one point the trench he was in took a direct hit from German artillery, his platoon was decimated around him. It was desperate stuff, but he refused to retreat, somehow keeping his telephone working, directing in British artillery fire and alerting HQ where reserve troops were urgently needed to help hold the line. He wrote home describing the incident:

“The Germans tried many counter-attacks but were smashed by our artillery before they reached us. If they had reached our trench, they would have got a warm reception as we were well prepared to meet them. I had my rifle in position with a stack of ammunition by my side and a few bombs ready to greet Hans and Fritz. All was going great the next day and Fritz was pounding away at what he thought was our trench not having spotted our position as I thought, when all of a sudden “Bang! Bang!! Bang!!!” and into our trench came some of the Hun’s shells, and missed me by a miracle but blew my haversack 5 yards and riddled it and its contents with holes. My biscuits were made into flour and my bully beef into mincemeat. It was raining most of the time, and everything was mud and water, and the cold nights without overcoats or any warm clothing was very cold.”

His letter is quite up-beat in tone, he tells of the impact on himself, but doesn’t mention to Frank the fate of his comrades in the trench. His diary is far briefer on these events, a cursory but sobering note which reveals the true toll:

Oct 5: “Our platoon about 13 strong. Many prisoners taken and many dead lying around.”

Remember a full-strength platoon is 55 men. Bert’s platoon has therefore been sorely hit by casualties.

When, in 1918, Gordon Coates wrote to the Gadds, he talked about an incident involving Bert which is most probably this moment. The casualty rate differs, but that inconsistency is understandable given that at the time, in the midst of the action, Bert would not have had as clear a picture of casualties as Coates did with the hindsight of several months. Coates says of Bert: “He did a very brave thing in the battle of Ypres in October 1917. A whole platoon was killed with the exception of two, he stuck to his post and kept his telephone going and got assistance and reinforcements up. Thanks to his pluck and bravery we held our ground and beat the enemy badly on that occasion.”

Australian soldiers in newly dug trenches on Broodseinde Ridge as they consolidate to hold the newly won ground. This is to the right of the Kiwi battle sector.

The success of the assault in gaining its objectives tends to mask the cost on the Aucklanders.

Although this attack had been an archetype of Plumer’s bite and hold, advancing the line by more than 1km, the losses had still been considerable. The New Zealanders suffered an estimated 1800 casualties, 500 killed outright or mortally wounded on the battlefield – roughly 25 per cent. And in Bert’s 1st Auckland Battalion, because of the difficulties they had encountered and the need to clear the British sector as well as their own, the casualty rate had been over 40 per cent.

On the first day of the operation initial reports back to Brigade headquarters had given senior officers a scare – the objective was taken but only 35 men remained alive from 1st Auckland they heard. Brigade Major Nathaniel William Benjamin Butler Thoms made haste into the battle zone to see first-hand and found Coates and 1st Auckland safely dug in, diminished in strength, but not so drastically reduced in number as feared and firmly in place, not intending to be moved an inch by German counter attacks.

At the end of it all, however, having charged across a bog, uphill through churned up mud that had once been farmers’ fields, smashing past strongpoints and pill-boxes, fighting hard all the way to their objective and seeing off wave after wave of counter attacks, the men were exhausted. Eventually the Aucklanders were relieved by British troops and 1st and 4th Brigades were pulled back to recover. Bert wrote:

Oct 5 & 6: “Relieved by the Tommies ... arrived at bivouac near Ypres at 5.30am, very tired, wet and cold. Received hot meal and issue of rum and a blanket and turned in to sleep under a canvas cover.”

He and the other Kiwis may just have gone through a searing experience and achieved what the high command had demanded. But rest and recovery were not on the agenda. A day after being relieved from the front-line trenches they were back to work fatigues - carrying timber for road making for days on end like mules.

The quality of mercy

German prisoners in a holding compound at Hoograaf behind the British lines on October 5, the day after the Broodseinde assault.

It is worth going back to the moment when Bert took his German prisoner – writing in his letter to Frank:

“I beckoned to him to come out of the hole, but he began gesticulating and I could see that he thought I would bayonet him, as evidently they are told that we take no prisoners, and he was scared out of his wits by our shell-fire like a rabbit. He was little more than a boy. I made him drop his equipment and I pointed in the direction of our lines ... and off he went with his hands above his head.”

Back in April, after his first experience of being in the front line and learning to cope with the stress of shells and bullets whining around him, he was tired and a bit angry. He wrote of the Germans: “they will fight as long as they have ammunition left in their rifle, but as soon as they are confronted with the bayonet, they have the cheek to put up their hands with “Mercy! Kamarad!” Well I will have to finish as I am at the end of my tether, besides at the bottom of the page.”

He sounded like a man who would not show mercy. But when it came to it, on that Ypres slope, his basic decency won out. Despite the danger he was facing, seeing comrades cut down, feeling the fear and the adrenaline of battle, nonetheless he showed restraint, even compassion to the young German he encountered. And that says something about his character.

Other New Zealanders that day on the hillside of Gravenstafel were less forgiving.

Burton, who, remember, served in the Auckland battalion and saw events first hand, tells us that when Kiwi soldiers came across Germans with their hands in the air and calling for mercy that “sometimes quarter is given; at other times there is only the shriek of agony as the bayonet goes home.”

Burton gives a summary of the Gravenstafel action, including a somewhat florid allusion to the Trojan war, but his views on the character of the average Kiwi soldier and what motivated them, is interesting:

“All night the attackers had lain miserably in the drizzling rain, heavily shelled, cold and sleepless. Vitality went low. As the barrage opened they moved forward. At once there was a transformation, a glow of feeling as the immensity of the whole thing entered into and lifted up a man's whole being. They pass the swamp and the German barrage — with loss. They encounter the first opposition, and see comrades killed and wounded. Rage enters in — a cold, silent, terrible rage. Men stalk on up the torn hillside, conscious of danger, but disdainful of it. They feel their strength is that of ten, and that their advance is inevitable and resistless — and it is so. There is a great exaltation of soul and a wonderful consciousness of power. So Hector must have felt when the Trojans stormed the Grecian Wall and carried fire and storm through the camp and to the ships. In some the elemental blood-lust comes to the surface, and they kill the enemy who bravely resist, they kill the prisoners whose surrender they have accepted, they kill the wounded lying helplessly in the shell-holes. One man boasted after the battle that he had killed no less than 20 of the enemy, most of them wounded and prisoners. Others coldly and terribly do their duty, killing if necessary, but showing mercy if it be possible. Others again fight with cheerful good humour, shooting Huns as if they were taking wickets. Some fight for glory, some that a woman back in New Zealand may perchance feel a thrill of pride for some deed done this day, but most because the task is there and it is their duty to do it. In the hour of advance and victory the spirit of the brave is always the infectious spirit.”

-web.jpg)